Defending the celebration of death

- Guest Post

- 2

- Posted on

Lord Sutch tackled the celebration of death in his recent post. I’m inclined to agree with his final thoughts, but specifically in a New Zealand context.

Lord Sutch tackled the celebration of death in his recent post. I’m inclined to agree with his final thoughts, but specifically in a New Zealand context.

In a modern, civilised society we shouldn’t celebrate death, regardless of the status or acts of the deceased. I agree because I think it’s true in New Zealand, but I’m hesitant saying that on behalf of others.In New Zealand, we are lucky enough to not be constantly at war with other nations. We have no strong political disagreements with other nations and to the best of my knowledge we have only entered war where strategic or diplomatic alliances have required it. Even when we do send troops abroad, it is usually met with the disapproval of the public.

Other nations are not so lucky. While I’m not going to wade into who deserves what, or which countries want natural resources from whom, I will note people are products of their environments. There is always a general public who didn’t make the decision to go to war, but none-the-less have to live with the decision.

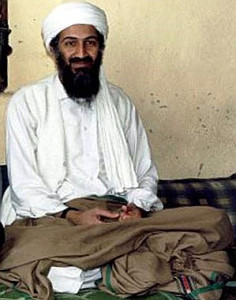

I was listening to an episode of This American Life recently, a journalist was speaking about her experiences when Osama Bin Laden was killed. She was confused that people of her age (late 20’s, early 30’s) had a reasonably muted reaction, the generation one step down (late teens to early twenties) went gleefully bananas; the kind of bananas where there was celebrating in the street, burning effigies, and drunken parties ‘til dawn. And she couldn’t understand why. Why, with such a small age difference, did her generation express a small amount of joy that the war was over, and those a decade younger celebrated so overwhelmingly?

I was listening to an episode of This American Life recently, a journalist was speaking about her experiences when Osama Bin Laden was killed. She was confused that people of her age (late 20’s, early 30’s) had a reasonably muted reaction, the generation one step down (late teens to early twenties) went gleefully bananas; the kind of bananas where there was celebrating in the street, burning effigies, and drunken parties ‘til dawn. And she couldn’t understand why. Why, with such a small age difference, did her generation express a small amount of joy that the war was over, and those a decade younger celebrated so overwhelmingly?

The journalist went out and asked a bunch of people, and it soon became clear that for this younger generation, Osama was the greatest villain they’d ever known. For their entire adult lives, their country had been at war with Osama. For many, their first awareness of international news, or in some cases other countries, was because of 9/11. It was the defining moment of their formative years. It marked a stark separation from the comparative safety of childhood with the fear of adulthood, the understanding that sometimes there is a monster under the bed.

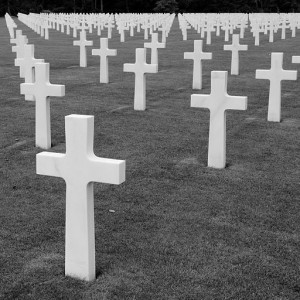

For people who grew up like this, who heard it on the radio and TV every day for over a decade, who saw friends of friends, family members and neighbours sent off to a war, maybe it is acceptable, or at the very least understandable, to celebrate death. The man who terrified their nation was gone. The monster under the bed had been pulled out of a dark hole and executed.

For people who grew up like this, who heard it on the radio and TV every day for over a decade, who saw friends of friends, family members and neighbours sent off to a war, maybe it is acceptable, or at the very least understandable, to celebrate death. The man who terrified their nation was gone. The monster under the bed had been pulled out of a dark hole and executed.

So I don’t think that we can or should be so quick to judge. I don’t agree with celebrating death, but I haven’t been in a situation where my country has been overrun with that sort of rhetoric for a decade either. The United States has had this burned into their national psyche. And as New Zealanders we are lucky enough not to be in that position.

Good little essay. And, of course, whatever the merits or pitfalls of punitive killing, there is also preventative killings, in that there are some people whose deaths prevent them from continuing to killing others, which is another natural trigger to celebrate their death. The world suddenly seems just a little bit better when a Hitler or an Osama Bin Laden has just died.

Thanks for your comment Duke. I think I’m even less comfortable with the idea of “preventative” killings than I am retributive. If we reach a stage where we are punishing people for crimes we assume they are going to make then we are in a police state and the libertarian in me is frightened of that prospect.

I understand what our guest author is trying to say – that in my peaceful little New Zealand bubble it’s very easy for me to sit piously and state “no celebrating of any death” when I’ve not been hurt by war, but isn’t that still a standard we should all aspire to? Just because we are affected by something, doesn’t mean we have to give in to it.