Why we should remember them

- Erin Reilly

- 0

- Posted on

It was freezing. It wasn’t one of those nice chilly I-just-went-to-the-snow-and-had-a-bundle-of-laughs-wearing-pompom-hats kind of freezings either; more like the kind of deathly freezing that burrows itself deep deep down into your soul and numbs you from the inside out, despite how many black Kathmandu jackets you’re wearing. Hundreds of people stood around in silence, in a crowd but still quite separate from each other. The silence was an odd sort of quiet, one that felt deeply foreboding yet still with a high degree of anticipation. Then the men started marching.

It was freezing. It wasn’t one of those nice chilly I-just-went-to-the-snow-and-had-a-bundle-of-laughs-wearing-pompom-hats kind of freezings either; more like the kind of deathly freezing that burrows itself deep deep down into your soul and numbs you from the inside out, despite how many black Kathmandu jackets you’re wearing. Hundreds of people stood around in silence, in a crowd but still quite separate from each other. The silence was an odd sort of quiet, one that felt deeply foreboding yet still with a high degree of anticipation. Then the men started marching.

When I was a nine-year-old Brownie, marching in Wellsford’s dawn service followed by munching on sausages in bread down at the RSA formed my Anzac Day tradition. Mum never let me wear long pants during the parade and I normally had to take my jumper off too. The old soldiers had their medals; I had my Brownie badges.

When I was that young I knew the basics. Old men and various other people around the community got up at sparrow’s fart and marched down Port Albert Road bearing wreaths and wearing poppies to honour the soldiers who’d served in bygone wars. Aside from a period of time when the moody teenage version of myself preferred sleeping in on her day off over remembering the fallen, I’ve pretty much always respected the memory of Anzac Day.

It helped that my dad is a history sponge. As a young family we took regular visits to any museum we could get our feet in, mostly to teach small impressionable minds but also to feed Dad’s hunger for more of the past; he’s like a cute kid in a candy store when he’s wandering around a museum. My brother took after Dad on the knowledge front. I’m not as gifted in that area. Ask me what I learnt in Bursary History. I have no idea.

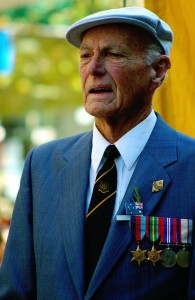

For me (at risk of sounding uneducated), Anzac Day doesn’t mean facts, figures, dates and battles; it means emotions. Standing in cold silence at the Auckland Museum dawn service and watching the old soldiers shuffle in procession towards the Cenotaph makes me tear up. These men aren’t brave soldiers any more. They’re old men riddled with grief and burdened with memories that have been banished to a padlocked part of their minds, and which many will take with them to their graves. These are men who might have been just 17 or 18 – still children – when they went to war. Men who were ordered to kill when just weeks earlier they’d never even seen a gun. Men who learned to accept the sound of gunfire as a permanent soundtrack to their dirty, hungry and frightened lives. Men who became the closest of friends with the men fighting beside them, then left them in the midst of battle in the throes of death. Men who went along to a war that wasn’t theirs and returned to their country as heroes – but to their wives as shadows of their former selves.

I think about my modern-day interactions with war and I immediately think Saving Private Ryan and the six o’clock news. We’re not that bothered by war anymore; even when the lovely Hilary Barry warns us that the following story could be shocking for some viewers, our eyes and ears perk up. But when I take the time to imagine what it might have been like to farewell my husband having only been married 13 months, or what it might have been like to face the enemy who has the same fear in his own eyes then shoot him dead before he gets the chance to shoot me, the emotional sacrifice becomes more startling.

This Anzac Day I’ll be heading to the Auckland Museum dawn service again, mostly to gaze at the old soldiers. If you’re keen to join me, it starts at 6am on Friday the 25th of April. Bring your tissues. Or you can use some of mine.