Peak peak Rumination 11: Blessed with certain gifts

- Morgan Davie

- 1

- Posted on

It’s not too late to catch up with the #TwinPeaksRewatch! Check the schedule at the bottom of this post!

This week our the #TwinPeaksRewatch is up to episodes 17 and 18 but instead of diving into them, this entry by Amanda Lyons is delving into some unfinished business: the aftermath of the climactic events that have just unfolded.

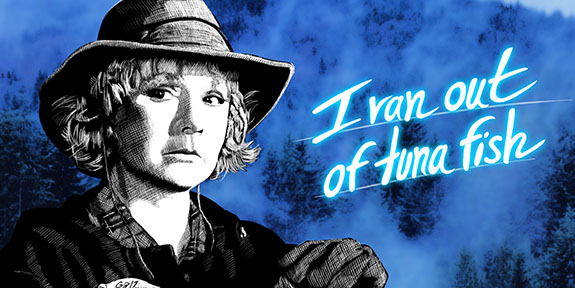

Illustration by Grant Buist (@fitz_bunny), check out his strip Jitterati.

You’ll also find below the details of the original NZ screening of these episodes, courtesy Paul Scoones.

Letting Leland off the hook…?

I love Twin Peaks; I love its genuine sense of otherworldliness, and its combination of sinister surrealism with the logically unfolding mystery of the police procedural. The tension between the competing needs of these genres – crime fiction with ‘Lynchian’, if you will – while not always satisfactorily resolved, often produces magic.

And yet, I have always been troubled by the crucial event at the rotten heart of the story: a shocking (yet at the same time, depressingly common) act of sexual violence, elevated to the realm of the supernatural. And while we do learn the answer to the question, “Who killed Laura Palmer?” the issue of who may be responsible remains troublingly murky.

Twin Peaks (as with much of David Lynch’s work) is strongly concerned with doubles and shadows. At the character level, this shows in double lives (most clearly represented in Laura Palmer’s good girl/bad girl divide, but also by many other residents of the town) to possession – two spirits contained in one body, eg, Leland Palmer/killer BOB, Mike/Philip Gerard.

The show also encompasses divides or opposites at a more meta-level, in its mash-up of genre requirements and auteurism. As Morgan Davie observed in Peak peak rumination 5, Twin Peaks walks a tightrope between police procedural/crime drama, soap opera and surrealist madness. But I would argue that the genre of crime fiction looms largest, providing the main ‘skeleton’ that contains the action of the narrative.

While all story-telling is, essentially, an act of voyeurism, crime fiction is especially compelling; crimes represent the point at which private lives explode into the public arena. When a crime is discovered, public institutions – the police, the courts, the hospitals – become involved in personal matters, the curtain is pulled back and secrets exposed for all to see: blackmail, fraud, affairs, violence, sexual abuse and murder.

This makes crime extremely fascinating, as those in thrall to countless story-tellers from Agatha Christie to Robert Durst can attest. However, while women are the largest consumers of crime fiction, it is also a genre that can be uncomfortable for women to consume, because so very much of it is focused around violence towards us and our portrayal as victims.

Of course, it would be simplistic to argue that the representation of these things is in itself misogynistic or against women, especially when we live in a world in which women are often the focus of violent crimes. Personally, I’m with Julie Bindel who has argued that what matters is the way the violence is presented – whether it has a context and a point that is not to titillate or pornographise.

Now, Laura Palmer’s murder is obviously somewhat fetishistic, but I don’t feel it to be presented in a way that is titillating or pornographic (I’m not as sure about her ‘bad girl decline’, although, to be fair, sexual abuse victims do sometimes react this way in the real world). Her murder is obviously shocking and upsetting, both to the denizens of Twin Peaks and to viewers, and the revelation of Laura’s father Leland as her rapist is genuinely horrifying.

I was more perplexed by what I felt was the show’s outsourcing of responsibility for Leland’s actions to an external actor – killer BOB.

As we all now know, (SPOILER ALERT for those who don’t!) BOB was an evil entity, a revenant of a serial killer and rapist who used to live near Leland’s grandfather when Leland was a child. He had molested child-Leland, and the two had shared a twisted bond ever since, with BOB possessing Leland’s body seemingly at will. (After being forced into suicide by BOB, Leland confided in his dying breaths that he never knew when BOB was in control of his body.)

It was BOB who molested Laura via Leland, and he also wanted to take possession of her body the same way he did with her father. Ultimately, however, he killed her instead.

The final unravelling of this mystery leads Agent Cooper, Twin Peaks’ Sheriff Truman and forensic analyst Albert Rosenfield to debate over whether BOB was real, or simply a manifestation of twisted desires that Leland couldn’t face up to. Although they don’t arrive at an agreement, Albert Rosenfield offers a conclusion of sorts when he says, “Maybe that’s all BOB is -the evil that men do. Maybe it doesn’t matter what we call it.” (Language that, intentionally or not, enshrines men as the ‘doers’ of evil and women as the invisible ‘done’.)

This denouement, like that of American Psycho, allows either possibility – BOB is responsible, or Leland is responsible. It’s also entirely possible that both interpretations are correct at the same time. But as a viewer, I felt dismayed and troubled by these philosophical musings on Laura’s rape and murder.

This discomfort, I think, stems in many ways from the clashing of the genres. You see, the thing about crime fiction is that it tends to be very comforting. Whatever terrible things happen within its strictures, the story usually results in resolution and justice (unlike so much of real-life crime – which is perhaps why it is so popular.)

In line with this, motivations in crime fiction are usually fairly clear; even the most evil deeds often have rational explanations, ranging from simple greed to the complex effects of an abusive childhood. Criminals offer fascinating psychological case-studies, whether they are bluntly psychopathic, or noble characters with a fatal flaw and/or inescapably bad circumstances.

Essentially, crime fiction shows the movement of the public, of structure, of solution and order, into the world of the private, the isolated, the invisible and the chaotic.

But Lynchian narratives follow an opposite trajectory – the withdrawal of the public, structured self into an internal landscape of dreams, illogic and mysticism. Any event that takes place in this setting becomes almost pointilistically individualised, unique; an island – and somehow at the same time, atavistically universal.

Laura’s murder (which, let’s not forget has been chosen by the show’s creators as its fulcrum – why this in particular, and not some other kind of crime or murder?) stems from an act of father-daughter incest, a crime that occurs in a crossroads between the public and private; where dark desires intersect with the cultural reality of male dominance over and entitlement to women and children within the nuclear family. For this reason, accountability is to some extent both individual and social. But the introduction of killer BOB strips Laura’s death of this social and political context, with the effect of reducing it to the result of an external and free-ranging evil.

So while I was glued to the unfolding of the quest to find Laura’s killer; compelled by the Stygian, murky evil that covered the town of Twin Peaks in an insidious mist; and captivated and terrified by killer BOB – and while the show also takes place in the real world as well as the world of the Black Lodge, the White Lodge, and the Red Room, meaning Leland will be seen as the true perpetrator by most people in the town (if not the investigators – and the viewers) – I felt that Laura Palmer herself was, in the end, let down by the ultimate reveal and its seeming dearth of earthly accountability for her abuse and death.

And yet, strangely and sadly enough, perhaps the unresolved resolution of Twin Peaks is less fantastical and more like real-life than a TV show like Law and Order.

Amanda Lyons (@MrsMeows) is a Wellington to Melbourne expat with an inordinate fondness for Garfield and an abiding interest in what popular culture reveals about our social psyche. She blogs at Mrs Meows Says.

—-

Grant Buist’s livetweets of these episodes (click on a tweet and scroll down to read the whole sequence):

Episode 17, aka Episode 2.10, aka 'Dispute Between Brothers' #TwinPeaksRewatch

— Fitz Bunny

(@Fitz_Bunny) April 1, 2017

Episode 18, aka Episode 2.11, aka 'Masked Ball', despite there being no literal masked ball in this episode. #TwinPeaksRewatch

— Fitz Bunny

(@Fitz_Bunny) April 1, 2017

—-

Listings for the original NZ screenings, thanks to ace researcher Paul Scoones:

Episode 17: ‘Dispute Between Brothers’

NZ: 22 July 1991; Tuesday 8:30-9:30 (US: 8 December 1990)

Agent Cooper and Truman bid farewell and a wake is held for Leland Palmer. Nadine may be able to go back to high school, Tremayne embraces fatherhood, and Audrey tells a new-found friend all about her ice cream preferences.

(Notes: no mention that this is the ‘final’, but replaced by an episode of the newly-launched Law & Order in the same timeslot the following week)

Episode 18: ‘Masked Ball’

NZ: 30 September 1991; Monday 11:05-12:05 (US: 15 December 1990)

Truman defends Cooper’s activities at one-eyed Jacks, Mrs Briggs worries about Garland’s disappearance and Nadine is besotted with Mike Nelson.

(Notes: billed as ‘Starts today’. Resumes after a nine week break. Moved to Mondays in a graveyard slot, as the last programme screened before closedown just after midnight)

(See Paul’s full post for more information on Twin Peaks in New Zealand.)

—-

Rewatch Schedule:

Join the hashtag #TwinPeaksRewatch

15 Jan: Pilot: Starting at the start

22 Jan: Eps 1 and 2: Damn fine cup of coffee

27 Jan: Eps 3 and 4: Laughing at prayers

5 Feb: Eps 5 and 6: Invitation to Love

12 Feb: Ep 7*: Biting the bullet

19 Feb: Ep 8: We want to help you

26 Feb: Eps 9 and 10: Bury her deep enough

5 Mar: Eps 11 and 12: Sometimes the Can-Do Girls Can’t

12 Mar: Eps 13 and 14: Missoula, Montana

19 Mar: Eps 15 and 16: That gum you like

26 Mar: Eps 17 and 18

2 Apr: Eps 19 and 20

9 Apr: Eps 21 and 22

16 Apr: Eps 23 and 24

23 Apr: Eps 25 and 26

30 Apr: Eps 27 and 28

7 May: Ep 29**

14 May: Fire Walk With Me***

21 May: NEW TWIN PEAKS!

* optional: The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer and The Autobiography of Dale Cooper books

** optional: The Secret History of Twin Peaks book

*** optional: The Missing Pieces

One thought on “Peak peak Rumination 11: Blessed with certain gifts”