Peak peak Rumination 17: Wow, Bob, wow.

- Morgan Davie

- 0

- Posted on

The #TwinPeaksRewatch schedule is at the bottom of the post with links to all these writeups as they happened!

This week’s piece on the final episode of the series, episode 29, was written by Alasdair Sinclair and Morgan Davie (that’s me). We had a big email conversation and Alasdair did an excellent job transmogrifying it into the essay below. We could have gone on much longer – this episode has so much to talk about – but I’m pretty happy with this…

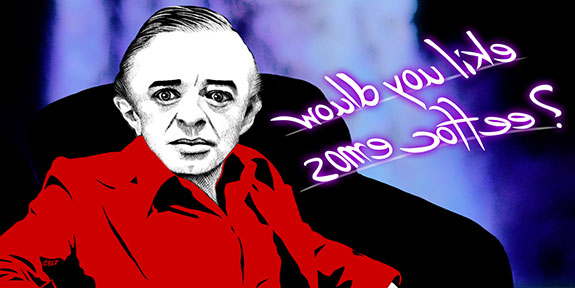

We again enjoy the lovely illustrative work of Grant Buist (@fitz_bunny), check out his strip Jitterati, and also his tweet-by-tweet reaction to watching the episodes, linked after the essay.

As per usual, you’ll also find below the details of the original NZ screening of the episode, courtesy Paul Scoones.

—-

Reading the erudite posts by each contributor in this series, it sometimes seems as if the differences in perspective and emphasis go beyond mere subjectivity, that each of us is in fact watching a different show altogether. From the very outset of the show there has been an otherworldly quality to the characters and their situations, allowing the tone and content to segue with relative ease between different dramatic strategies. Twin Peaks is the show where the FBI investigates the latest in a serial killing using the most advanced forensics as well as by throwing rocks at glass bottles. Alongside the nominal procedural of the FBI investigation there have been stories of drug smuggling, a tragicomedy of amnesia, the power struggle for the control of Ghostwood Estates, and a host of others. By drawing on so many diverse storytelling approaches, Twin Peaks destabilizes any attempt to use any single conventional or genre strategy for interpretation: no consistent logic applies. In narrative terms this just about destroys the basis of cause-and-effect, and nothing typified that more than the protean Laura Palmer, who truly seemed to be all things to all people, and so became the connective tissue in the community. Dale, in his purview as FBI investigator is the only other character with similarly wide connections to the community by the time Bob is unmasked.

Of the genre clashes, Windom Earle has been the most difficult to accept. We returned to this re-watch seeing him as deeply inappropriate concept for Twin Peaks. Earle drags an outside narrative into the show, locking Dale into external concerns when he should instead be turned to face the community he has all but settled into, completing the character arc that began when he first arrived at Twin Peaks and dictated how enraptured he was to his assistant Diane. Dale’s integration could have come at the moment when the town is, broadly, returning to normal after the trauma of Laura’s murder – aside from the spectre of Earle. As the commentators on Season 2’s second half have attested, Earle is a wildly mishandled figure: overexposed, played too broad, and incoherently written. His fate in this final episode – simply eliminated without fanfare by Bob at what seems to be his climactic moment – seemed to us a confirmation that his whole story has been a misstep.

Earle’s “incoherence” fits with the variability the commentary team has been identifying because he is not the logical construction of formulaic stories of any kind. Instead, we’ve all spent time considering the meaning of “oneiric”, because Twin Peaks has the illogical construction of a dream, where the system of meaning as a whole trumps the mechanics of each individual moment. The dream of Twin Peaks hinges on a simple question, to which each different subplot has eventually returned: what does it take for a good person to make a bad decision, and what’s left of them afterwards? Will Donna betray the trust of the shut-in she’s just met in order to learn more of Laura? Why, of course. Will Norma enable Hank’s criminal schemes? Under sufferance. Will Shelly murder Leo to escape from his abuse? Well, not quite. Will Audrey Horne sleep with her father to uncover the connection between One-Eyed Jacks and Laura Palmer? Fortunately not. Some characters have faced steeper trials than others, such as Josie choosing death rather than truly betraying Harry. The show refrains from making this question a moral one – we don’t judge James for succumbing to sexual allure and hence complicity in murder, but we pity him for thus entering the orbit of a nightmare.

In the logic of the dream, Earle represents Dale’s last obstacle before he can completely abandon the procedural onus of the FBI agent and accept the permanent star of Harry’s deputy, settle down with sweet Annie and enjoy a life of donuts and damn fine coffee. Dale, like the other characters in the show, must face his own moment of decision: what bad thing will he do for what good reason? Inexorably, the last few episodes have led him to the Lodges and from the day this episode first aired, people have been advancing theories about how, exactly, Dale failed within. Many have turned to Hawk’s reference many episodes ago to “imperfect courage”, and tried to point out flaws in Dale’s courage: perhaps out of his concern for Annie, or his reaction to the doppelgängers. More have come up with even more elaborate explanations, trying as they do so to make sense of the chilling final image in this series, the unresolved crisis that has hung over this show for two and a half decades.

As an outsider, Dale began with no investment beyond professional pride, and over the course of the show has retained his benevolent detachment, never allowing the stakes to become personal for him. In the illogic of the dream, Earle is not Dale’s antagonist, he is merely the catalyst that allows Dale to finally face his own moment of truth. In other words, it’s easy to be the paragon of virtue when it costs you nothing, and Earle is not here to defeat Dale, merely to force him to make that crucial decision. This is why there are no calls for forensic expertise – there is no mystery to solve, no unknown fact to uncover, no procedural purpose to investigating. In the illogic of the dream, Dale must be made ready to decide how to finish his confrontation with evil.

Although with the benefit of rewatching we understand with greater clarity the extent to which Earle was mishandled, we have softened on his role in proceedings in light of his oneiric function. Earle was obviously set up as a foil counterpart for Dale, in tune with the Lynchian iconography of duality and doubling that suffuses the show: another FBI agent/mystic, at home in both the mundane world and the heightened reality lurking in the woods. We see how he provides an opportunity to break Dale down to a deeper level, preparing him for greater challenges. That dark past in Pittsburgh is an unhealed wound, and the show has given indications right from the start that Dale is not in command of himself to the extent he would like; his obvious fixation on Audrey Horne seems to us a sign of deep vulnerability, and his repeated hesitation to engage with the Log shows his shamanic powers are more willed than intuitive.

Whatever this is, it isn’t lack of courage; but it is an imperfection, a lack of self-belief perhaps, a self-doubt, certainly a lack of wholeness. Dale is not resolved within himself. And with that in mind as a framework, doesn’t the whole strange dream of season two seem to embody that same lack of internal resolution? Dale decides to face Earle alone, leaving behind his friends and his allies, because he believes by this point that he can’t defeat Earle. He subcontracted out the battle of wits to Pete, of all people, instructing not him not to win the game but to lose as painlessly as possible. Faced with the ultimate decision of whether to defeat evil, Dale decides not to.

In doing so, Dale finally solves the real puzzle of Laura Palmer. For her, self-sacrifice was the only way to thwart Bob and she realized that was a price she was willing to pay, but the puzzle has always been why. For Laura, the love she felt for James, or Bobby, or Donna, was ultimately less powerful than her belief in herself. Laura was able to be everything to everyone because it didn’t affect her perspective on herself. Dale, consistently cheery, quirkily brilliant, ultimately did not believe he could win, and so, lost. Laura knew her value, Dale believed he had none. Laura could be the centre of Twin Peaks, but Dale cannot.

So return to the final moments of Windom Earle. He has defeated Dale, but his killing blow is reversed and Bob appears, declaring that Earle was wrong and announcing that he will take Earle’s soul instead. In a burst of flame he does so, and almost immediately after we see movement behind the curtains, and the shadow Dale comes into the room, joining Bob to laugh beside the shell of Windom Earle.

It seems so obvious now: the Dale doppelgänger is Windom Earle’s soul.

Not, to be clear, Windom Earle himself. Earle is gone and done; that conflict is resolved. Dale’s failures and fractures no longer turn on his relationship with Earle, because Earle’s catastrophic failure of judgment regarding the Lodges diminished him before Dale. Dale’s failures are now interwoven with the secret world alongside Twin Peaks. Windom Earle was the sacrifice needed to bring Dale and Twin Peaks together at last.

Alasdair Sinclair wrote Peak peak Rumination 3, and his film crit is at My One Contribution to the Internet. Morgan Davie has been here the whole time, haunting this series of posts like a portrait of Laura Palmer under the closing credits.

—-

Enjoy Grant Buist’s livetweet of this episode (click on the tweet and scroll down to read the whole sequence):

Episode 29, aka Episode 2.22, aka 'Beyond Life and Death', aka WHAT THE FUCK WAS THAT? WAS THAT *IT*? #TwinPeaksRewatch

— Fitz Bunny ⭐️ (@Fitz_Bunny) May 7, 2017

Listener magazine listing for the original NZ screening, thanks to ace researcher Paul Scoones:

Episode 29: ‘Beyond Life and Death’

NZ: 16 December 1991; Monday 11:05-12:05 (US: 10 June 1991)

Cooper and Truman attempt to head off Windom Earle at the Black Lodge to save the life of Miss Twin Peaks. Nadine Hurley enrols in the school of hard knocks.

(Notes: final episode, screened just over six months after the US. Feature article ‘Cherry Pie-Eyed’ by Jenny Wake, about Twin Peaks fandom)

(This brings to an end Paul’s notes on original screenings, as it is the last TV episode of the original run! See Paul’s full post for more information on Twin Peaks in New Zealand.)

—-

Rewatch Schedule:

Join the hashtag #TwinPeaksRewatch

15 Jan: Pilot: Starting at the start

22 Jan: Eps 1 and 2: Damn fine cup of coffee

27 Jan: Eps 3 and 4: Laughing at prayers

5 Feb: Eps 5 and 6: Invitation to Love

12 Feb: Ep 7*: Biting the bullet

19 Feb: Ep 8: We want to help you

26 Feb: Eps 9 and 10: Bury her deep enough

5 Mar: Eps 11 and 12: Sometimes the Can-Do Girls Can’t

12 Mar: Eps 13 and 14: Missoula, Montana

19 Mar: Eps 15 and 16: That gum you like

26 Mar: Eps 17 and 18: Blessed with certain gifts

2 Apr: Eps 19 and 20: Halfway through living it

9 Apr: Eps 21 and 22: And the hippie too

16 Apr: Eps 23 and 24: It’s a pretty simple town

23 Apr: Eps 25 and 26: Verses of the same song

30 Apr: Eps 27 and 28: Which way is the castle?

7 May: Ep 29**

14 May: Fire Walk With Me***

21 May: NEW TWIN PEAKS!

* optional: The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer and The Autobiography of Dale Cooper books

** optional: The Secret History of Twin Peaks book

*** optional: The Missing Pieces