The Spy Who Didn’t Love Me

- Ali Ikram

- 0

- Posted on

The following text was delivered as an address at the Muslim World Forum, Aotea Centre, 23 November, 2013. The forum marked eight years of relationship building between the Office of Ethnic Affairs and New Zealand’s Muslims.

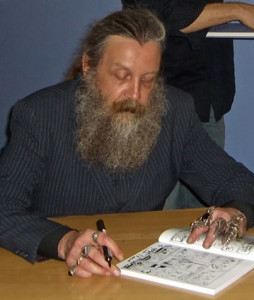

My story begins when I grew a beard. It wasn’t large, and certainly had no political or religious motivation. I simply put down my razor during the summer holidays and my face did the rest. My girlfriend liked it, so the beard stayed.

Yet unwittingly, my personal grooming was about to pull me into a vortex of serious global issues beyond my control. It was to see my name mentioned in Wikileaks twice and land me with an SIS record that, to this day the department will not let me see.

I’ll get back to the face forest later. But by way of introduction, my name is Ali Ikram and I’ve been a journalist for 14 years. I’ve spent the last four of those years on Nightline. I meet a lot of Muslims in the course of my work. That’s because in the course of my work, I take a lot of cabs.

In the short ride between work and home each night, we cover a lot of ground. The drivers are most often Pakistani and by extension, Muslim. The conversation is always entertaining. The questions drivers ask are often very similar. Here is a selection posed to me over the years.

- Are you Muslim? I could say yes and make the ride easier. But I think to claim you are part of a particular religion, one really should practice most or all of its tenets, and I don’t. This is despite holding the belief that I am on some form of spiritual journey we’re all on whether we recognise it or not.

- Where are you from? I’m from Christchurch. But that answer never suffices, so the embellishment of my father is from Pakistan and my mother is English must be added before we can move on to question number three, which is:

- Are they still together? The answer to this question is “yes” but that it is posed suggests to some the thought of a Pakistani marrying a non-Pakistani and constructing a successful union out of the situation is like the successful pairing of a badger and a unicorn.

- Do you speak Urdu? No, for some this is the biggest disappointment. “Why don’t you speak your own language?” said one, as if I had been mute since birth only able to communicated in gestures and grunts because no one had taken the time to sit me down and bestow on me the blessing of a sub-continental language.

- Did you marry a Pakistani girl? No, my wife is a New Zealander who is half-Italian half-Kiwi and to complicate matters, born in Canada. My favourite driver was the one who on hearing this looked wistfully out the window at the lights of Mt Eden Road and said “I could have married Kiwi girl once, she loved me so much.”

- And finally only one cab driver asked whether I am circumcised. For some reason I refused to answer that. I must have been shy that night.

Don’t get me wrong, I love these guys. They do a tough job. They see a lot, and much of it probably clashes hard against their ideas of how the world should be. I mention them only to demonstrate how culture is a series of preconceptions and expectations of behaviour. For these men, I fulfil very few ideas of what it is to be Pakistani and none of what it means to be Muslim. Culture can be great, keeping people together and providing security. I should say, it can be great when you are the ones defining what it is you are and what it is you do.

But it sucks when people who don’t understand you and possibly don’t like you are the ones telling the world what your culture or your religion is. Thank you for having me at the Muslim World Forum. So this is Muslim World. It looks like a side room at the Aotea Centre. I was hoping Muslim World would be a theme park like Disney World or Dream World. But what would someone who only knows about Islam from Fox News expect of such a place? To them it would be a theme park with no hot dogs, no beer, no music, no women’s ankles, no kites, no Adam Lambert, no Gaga, definitely no Miley Cyrus, no depictions of creatures alive or dead, no television, no wine, no shaving, no catfish, molluscs, crab, eating eagle and definitely no dancing. If all you knew about Muslims and Islam came second or third hand you might think it was a religion devised entirely to avoid doing anything, except growing beards.

I was telling you about my beard before. It is fitting that this event celebrates the good work of the Office since 2005 because that is the year I didn’t shave for a while. It was more crucially the year of the 7/7 London bombings. In those days I was working at TVNZ.

After the bombings, I went on a show called Agenda. It was one of those current affairs discussion programs. It wasn’t infotainment. It was a show for intelligent people about serious issues. But as I sat there listening to the way the bombings were being discussed, I found myself becoming increasingly annoyed. Algerian refugee Ahmed Zaoui had been brought on to explain Islam. He spoke the immortal words that perhaps some of you when interviewed by the media have spoken: “Islam is a religion of peace.” Of course, in TV, pictures and not words tell the story and when you say that sentence no matter how true it is, while surrounded in a story festooned with the injured and blazing wreckage, the words might ultimately come across as empty. Then some military expert from Wellington was trotted out and he complained that not enough Muslim countries had “apologised” for 9/ 11. Then Simon Dallow asked me if I was a Muslim in the ad break and I said I didn’t practice. He wanted me to explain that to everyone at home – but no one else had to avow or disavow their religious affiliations. In all of this I did something that I think may have tweaked a few people and got me noticed. In my fit of pique I thumped the table.

A few weeks after me and my facial fungus banged the desk I was off to America. It was a routine type of thing the State Department takes journalists on. I found myself with a bus load of Muslims heading for all manner of locales. In Santa Fe we visited a cult, in Minneapolis we met the union for migrant farm workers and in Kentucky I diverted the whole tour to pay my respects at the grave of Colonel Sanders. Locals told me some mourners, instead of leaving bouquets of flowers, leave little posies of chicken drumsticks on the KFC founder’s tomb. I met some great people. I met a Dutch Moroccan internet guru using technology to bring his community together and a hard-line Nigerian cleric, not doing anything with technology. His name was Saladin Yusuf and he railed against the US as the Great Satan, many of his friends did not believe he would escape from the country with his soul intact. The Americans just smiled politely and nodded and said “yah… yah …a lot of people think that.” That turned him round a bit. He had given the white devils everything he had with both barrels but instead of throwing him in a dark hole they had listened, agreed his opinion was a common one and taken him to lunch.

Everyone was turned around, except me. There wasn’t much to turn around. Some of the people on the bus couldn’t work out why I was even there. It was hard to explain to them that in the country I come from I am considered exotic. Of course, what happens when you are confronted by the act of defining yourself overseas, you inevitably become what you are. In my case that turned out to be – a Kiwi. I performed the Haka at the Council on Islamic Education and when I was told by one of the US guides that my problem was I was from a small country and had an inferiority complex, I replied “if I came with one, I certainly was not leaving with one.”

Before departing for America the US embassy gave me a letter to present at customs. It explained I was a guest of the State Department and was to be treated with the same respect extended to any other traveller. It got me thinking: If I was to receive the same respect as any other traveller, why did I need a letter? The oddness of the times was summed up with a sign at one of the interminable security screening areas, advising us all jokes were banned at that checkpoint.

Now, I like jokes. My theory is we live in an absurd world and to take it seriously only makes you more ridiculous. But I can see terrorism is real and not just real but frightening. No one here would dispute that. The 3000 killed in the World Trade attacks and the 49,000 Pakistanis who have died in acts of terrorism since – their lives were wasted. All died before their time. All died as victims in someone else’s war. Though everyone will remember how things were post 9 /11 and the climate of fear that issued forth. In these times, context began looking like justification and patriotism started being confused with the truth. But despite all that, the way I felt then and the way I feel now – and you might wonder the same is – what the hell has it all got to do with me?

I came home from America and got back to my life. Then one day in 2006, I was surprised to get a call from a man I had met while in the US. His name was Shabbir Mansuri, the head of a group called the Council on Islamic Education based in LA. Like all Pakistani visitors he rang from the airport wanting to stay at my house. Having just had our first child, I couldn’t oblige but was asked to set up a meal with young Muslims so he could meet and talk with them. So a few of us trooped along to Marco’s, a nice North African restaurant in Newmarket. But along with the usual suspects, there was an unexpected guest, a guy called Kaweem Koshaan who worked at the US embassy. The night passed without incident. Fortunately, no one said “I would like to see Shariah law introduced to New Zealand, could you please pass the bread” or “after coffee let’s give a worldwide caliphate a go.” I say fortunately, because what we said and did was being noted down by Kaweem and wired back to Washington. Thanks to Wikileaks we know that the US embassy’s conclusion on New Zealand was: “since the 1990s immigrants with limited language and educational backgrounds have come into an already established Muslim community with mosques, halal meat butchers and government services available in their native languages. If not carefully managed this could lead to the kind of insulation seen in some Muslim populations in Europe that can potentially serve as a breeding ground for home-grown extremists.” It appeared what was of most concern to the US was that the Muslims had a mosque, were making their own food and received equal access to state assistance.

Though it is true, there is a problem when people get isolated. It came to the fore in New Zealand after the London bombings. But in the situation here, the ones who had cut themselves off from society while harbouring extreme views and nurturing a desire to lash out at those who they deemed were contaminating the world were not young Muslims. They were two European teens. One was called Ross and the other was Jason. By all accounts Ross and Jason spent a lot of time isolated in their rooms on computers hanging out in white supremacist chat rooms. When you don’t meet a lot of people or the people you meet all agree with you, there is no-one around to defy your expectations. You are unchallenged. It’s very easy to dehumanise people who are simply not there. Anyone can be radicalised if they are impressionable enough, isolated enough and fed the idea they are good, someone else is bad and only through their intervention can the fallen world be redeemed. The thing that sticks out most for me about the story of Ross and Jason is not what they did in breaking mosque windows and painting slogans on the walls. The thing I remember most is they spent quite a lot of time sitting in the car park of the Hindu temple on Balmoral Road. They were on the verge of plotting revenge on completely the wrong religion, until they were moved on by a security guard.

It tells you that quite unsurprisingly ignorance is not based on accurate information. Fear too is an unreliable compass. The hunt for the enemy within can end up making you more enemies than when you began the search. If a New Zealander, born here, with no criminal record or isn’t even Muslim (should that matter) can be deemed worthy of surveillance, perhaps the SIS is barking up the wrong tree, routinely. After the Wikileaks cables were released I wrote off to the SIS to see my record that most people get to see. The request was declined. The service suggested it would be against the interests of national security and might harm our information sharing relationships with foreign powers. That decision was backed up by the privacy commissioner.

I did shave off my beard. I was offered a couple of weeks filling in on the Breakfast show, the only thing standing in my way was what was going on beneath my nose. When the beard went I’d like to say all discrimination in the world and the political problems that had so bedevilled it disappeared with the whiskers down the plug hole, but alas I fear they may have just gone underground. The Muslim community were the canaries in the civil liberties coal mine. We experienced what the rest of the world was in for a few years in advance. Now through the work of various whistleblowers, we have become aware of the extent of national and international surveillance. Though the issue has become a wider one facing not just one religion or individual citizens, but thousands of people with friendly states spying on sworn allies.

As a postscript: My beard may be gone but it was immortalised in our wedding photos and will live on to embarrass my kids for years, perhaps decades to come.

If you want to support the Ruminator, please consider making a donation via Givealittle.